Imagine two parents, Jenny and Elena. They’re similar in many ways. They both have four-year-olds. They both want to help their children get ready for kindergarten. They both read to their children every night.

But there’s a difference: Jenny and her daughter spend more time learning the letters of the alphabet, while Elena and her son spend more time playing sound games.

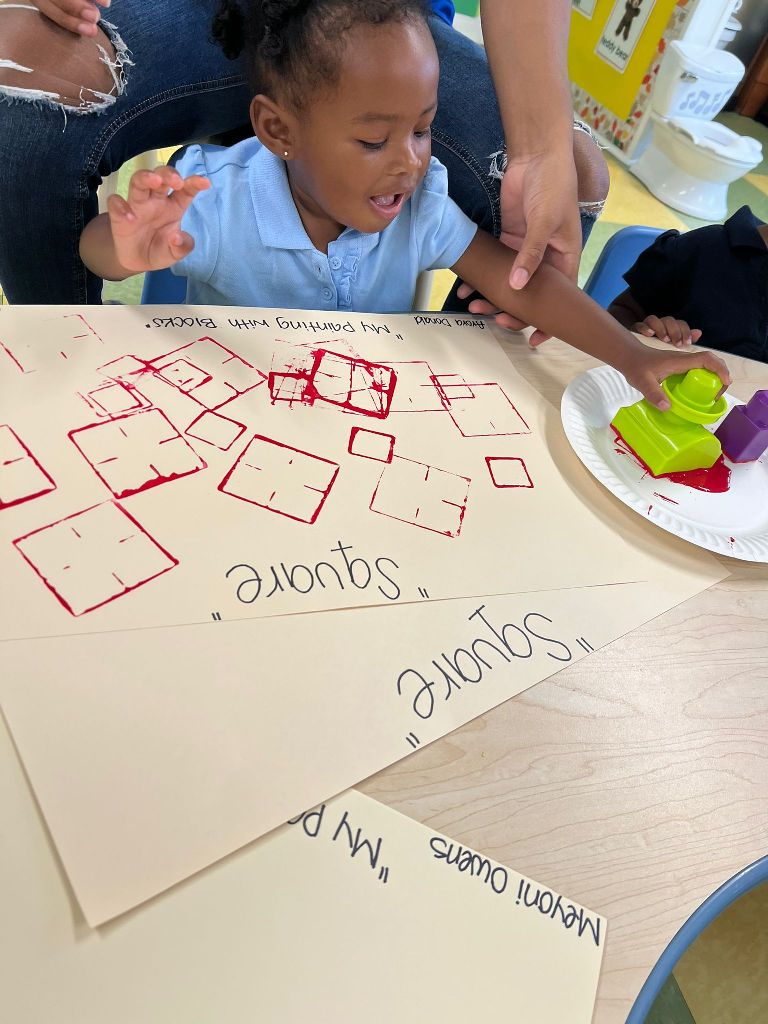

Almost every night, Jenny and her daughter play games with floating letters in the tub. “Can you find the letter B? What sound does the letter B make? How about Q?” By now, Jenny’s daughter knows pretty much the whole alphabet.

Elena has the floating letters but rarely uses them with her son. Instead, during bath time she and her son play word and sound games. For example, they’ll take a name like “Tony” and have fun with the sounds in it:

Tony, Tony, bo-bo-ney,

Bo-na-na fanna, fo-fo-ney,

Fee fi mo-mo-ney, Tony!

Or they play Apples and Bananas:

I like to ate, ate, ate ay-ples and ba-nay-nays

I like to ate, ate, ate ay-ples and ba-nay-nays

Sometimes Elena pulls out Shel Silverstein poems and hams it up:1

Sarah Cynthia Sylvia Stout

Would not take the garbage out!

She’d scour the pots and scrape the pans,

Candy the yams and spice the hams,

And though her daddy would scream and shout,

She simply would not take the garbage out.

They laugh and laugh as they exaggerate the rhyming. Sometimes they just keep going, rhyming words both real and imagined: peas, cheese, please, mease, fleas, gleeze, stupidese!

Elena and her son may be having more fun, but Jenny’s daughter is going to be better prepared for kindergarten. Right?

Wrong.

It turns out that being able to recognize individual speech sounds is incredibly valuable for incoming kindergarteners, maybe even more valuable than knowing your letters. This is because there are a total of 44 speech sounds in English, although there are only 26 letters. When you learn to read, you’re learning how to associate these 44 sounds with letters by following a complex set of rules. Familiarity with these 44 sounds gives a child a big leg up on the process.2

Wordplay helps children learn to recognize individual speech sounds. For example, children need to be able to hear and recognize both the consonant and the vowel sounds in the letter F. When you pronounce F out loud, you begin with “eh” and end with “ff.”

When we play with words, we’re learning the underlying sound architecture of the language. This is true whether we’re talking about English or another language.

Cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham has several great suggestions for word play:3

Here are a few others my kids loved:

As Willingham notes, these sorts of word games do double duty. In addition to helping your child learn speech sounds, they also learns that language is fun and worthy of special attention.4

Don’t worry that your child needs a certain amount of practice. In fact, they might come up with an even better game! Just follow their interests and have fun with it.

Play sound and word games that expose your child to a wide range of language sounds, while having fun.

Go find your child now and read them the beginning (above) and end of Shel Silverstein’s poem about Sarah Cynthia Sylvia Stout. Have fun with it! Here’s the end:

. . . At last the garbage reached so high

That it finally touched the sky.

And all the neighbors moved away,

And none of her friends would come to play.

And finally Sarah Cynthia Stout said,

“OK, I’ll take the garbage out!”

But then, of course, it was too late . . .

The garbage reached across the state,

From New York to the Golden Gate.

And there, in the garbage she did hate,

Poor Sarah met an awful fate,

That I cannot now relate

Because the hour is much too late.

But children, remember Sarah Stout

And always take the garbage out!

Sign up for my newsletter to receive one new article each week, customized to the age of your child. Just enter your email address below and click “Subscribe.”Email Address

Age of Children

Infant: 0—12 months old

Toddler: 12—36 months old

Preschooler: 3—5 years old

No kids these ages, but keep me informed