Preschool — it’s not just about the sandbox anymore. As elementary school becomes more rigorous, so does preschool. Children are expected to learn certain skills in preschool so that they are prepared for elementary school. Considering the limited time in a preschool setting and the pressure for success later on, where does play fit in?

Children are playful by nature. Their earliest experiences exploring with their senses lead them to play, first by themselves and eventually with others. The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) has included play as a criterion in its accreditation process for programs for young children. “They call it their work,” says Peter Pizzolongo, associate director for professional development at NAEYC. “When they’re learning and playing with joy, then it’s a positive experience. They develop a positive approach to learning.”

As children develop, their play becomes more sophisticated. Up until the age of 2, a child plays by himself and has little interaction with others. Soon after, he starts watching other children play but may not join in. This is particularly relevant to kids in multi-age settings where younger children can watch and learn from older preschoolers playing nearby.https://afa45dbdfb3d2b7624e18e0b9ab01f51.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.htmlADVERTISEMENT

Around 2½ to 3 years, a preschooler starts to play sitting next to another child, often someone with similar interests. This naturally shifts, through the use of language, to the beginnings of cooperative play. An adult can facilitate this process by setting up a space for two or more small bodies and helping children find the words to express their questions or needs.

Between 4 and 5 years, preschoolers discover they share similar interests and seek out kids like them. They discuss, negotiate and strategize to create elaborate play scenes; take turns; and work together toward mutual goals.ADVERTISEMENT

The preschool teacher’s role in the development of play is critical. “Parents should look to see that the teacher has organized the environment,” says Pizzolongo, “and is using her curriculum in a way that guides her to plan for how the children are going to be engaged in play. It really is a structured way of learning. It just looks like a different structure than what you would see in fourth grade.”

Children’s play can be divided into categories, but the types of play often overlap.

Through play, children develop skills they’ll use in their school years.

Both gross and fine motor development occur through play. When kids play outdoors, if they feel comfortable and supported, they’ll push themselves to new challenges and build motor skills. Developing fine motor skills, such as handling small objects, is a way for children to practice using their hands and fingers, which in turn builds the strength and coordination critical for writing skills. “When you’re a preschooler or toddler, your attention comes out in a different way,” explains Pizzolongo. “Your attention works best if your body is involved, as many parts of it as possible. So children learning to play where they’re physically engaged with materials and interacting with each other would work best.”

Children build language skills through cooperative play. Their success depends on their ability and patience in explaining themselves. Teachers repeat the words children say to help others understand. They also teach words about the objects the kids are interested in handling. Students may talk to themselves while playing side by side with other children and then begin to repeat what they hear or start talking to each other. This develops into back-and-forth communication about play, becoming increasingly sophisticated by age 4. Children will now set rules, have specific roles, express their interests or objections, and chatter about funny situations that occur in the course of play.

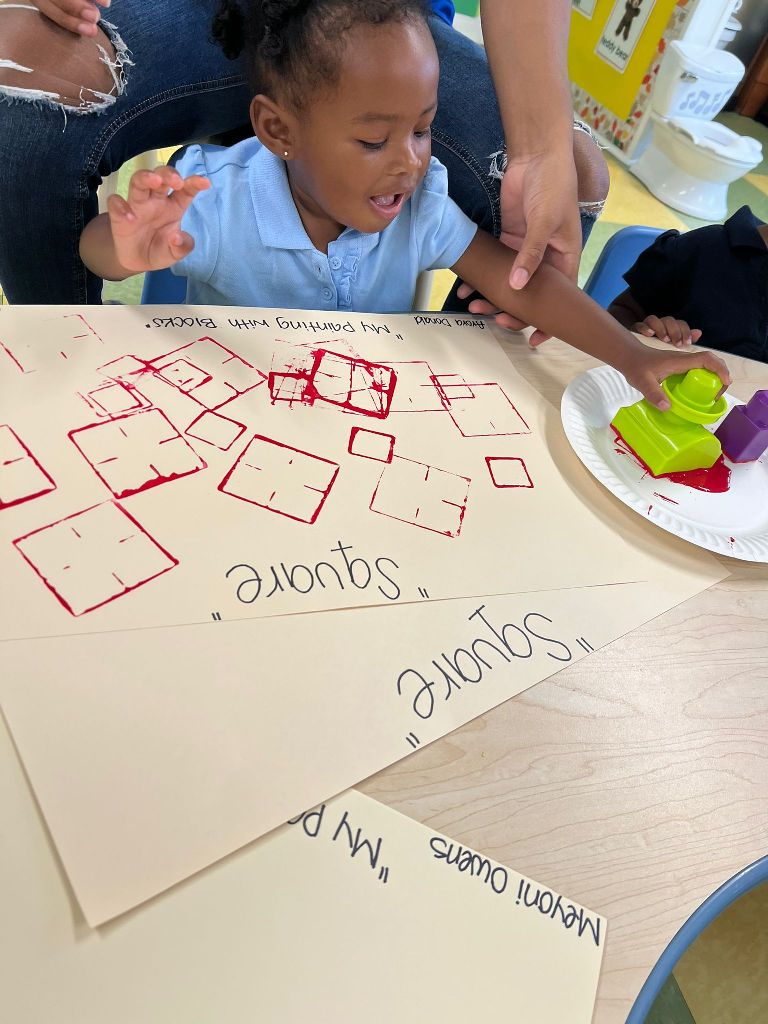

Play builds a strong sense of self-confidence. Trying to do a certain trick on a play structure or build with blocks is hard work for a preschooler. Teachers acknowledge these experiences by articulating what they observe and letting the preschooler absorb these accomplishments again. There are also therapeutic benefits to play that help all children. For example, understanding that a parent is going to work and will come back at pick-up time can be reinforced through a play scenario.

Listening, negotiating, and compromising are challenging for 4- and 5-year-olds. Though children at this age are still egocentric, or unable to think beyond their own needs, working with others helps them develop an awareness of differences in people around them. These experiences in preschool provide a foundation for learning how to solve problems and communicate with peers. Play also helps build positive leadership qualities for children who are naturally inclined to direct but must learn how to control their impulses.

For many school-age kids, their time outside of school will include solitary time spent plugged into video games and computers, so it is especially critical for preschoolers to have the opportunity to develop naturally in their play.

Julie Nicholson, an early-childhood instructor at the Mills College School of Education in Oakland, Calif., notes, “We know from decades of research that young children’s play is very beneficial for their development, so we have to look at such immensely important topics as the decrease in children’s outdoor play, the loss of extended periods of unstructured time for children to engage in imaginative play, and the toys being marketed to children that are increasingly violent, sexualized, and closed-ended.”

When you tour preschools you’re considering, ask about their philosophy about play. Preschoolers need opportunities to play, prepared spaces for them to explore and responsive teachers to support their learning. Such a setting prepares children not only to become students who will work with others cooperatively and approach learning with joy, but also happier people who will not lose their love of play.